How Apostle Elkana and Tito led Mwisho wa Lami ‘maandamano’

Apostle Elkana announced that he planned to lead maandamano on June 25 to commemorate victims of police brutality.

What you need to know:

- In Mwisho wa Lami, we’ve always viewed maandamano as something that happens far away in Nairobi and other big towns.

- On the day, I was at Hitler’s to appreciate the eminent panel of marriage experts, Tito, tried to talk about maandamano.

Why does the word maandamano elicit little emotions in Mwisho wa Lami? Besides those few isolated incidents when my enemies of development made a few boys drunk and gave them placards written “Mwalimu Andrew Must Go!”— usually right after exam results were released — we’ve always viewed maandamano as something that happens far away in Nairobi and other big towns. Not here.

Let me digress a bit.

One of the reasons I’m genuinely happy with CBC — sorry, CBE — is the glorious disappearance of the annual KCPE ritual. No more unnecessary competition and comparing schools. Today, all of us, heads of institutions are equal before God and the TSC. Nobody knows your mean score.

Now, back to our story.

While the country was murmuring about police brutality, and we teachers whispered in the staffroom about the unfortunate passing of our colleague Albert Ojwang, there was nothing officially planned in Mwisho wa Lami to mark the tragic events of a year ago. We were simply looking forward to a quiet public holiday: a day of chai, sleep, and forwarding memes on WhatsApp while watching other people protest on TV.

That has always been the routine. Until this week.

On the day, I was at Hitler’s to appreciate the eminent panel of marriage experts, Tito, who calls himself Gen Z, though he clearly is not one, tried to talk about maandamano.

“All Kenyans are having maandamano,” he announced loudly, “We too must do something.”

Everyone looked at him like he had announced plans to launch a rocket from Hitler’s roof.

“What do you want us to do?” asked Nyayo, frowning.

Now, Nyayo is famously sympathetic to the police, mostly because he once aspired to be one. Unfortunately, his academic journey ended in Class 8 with a KCPE score that was best described as spirit-led. Although he always says there was no money for secondary school, the truth is no school was willing to admit a boy who scored double-digit KCPE total marks.

“We must protest against police brutality,” Tito insisted.

Nobody replied. The message to Tito was loud and clear: You are alone in this one, brother.

But he wasn’t alone for long.

Shortly after, we heard a public announcement that shocked the whole village: Apostle Doctor Reverend Elkana, the Revered Spiritual Superintendent of The Holiest of All Ghosts (THOAG) Tabernacle Assemblies Sanctuary, announced that he planned to lead maandamano on June 25 to commemorate victims of police brutality.

According to those who attended his Sunday service, the Apostle declared: “If others are afraid, the church will stand with all Kenyans to tell the government to do what is right!”

On Monday, Elkana and Tito visited us in school.

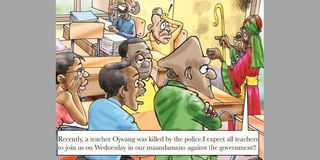

“Recently, a teacher — Ojwang — was killed by the police,” Elkana began after I reluctantly allowed him to speak in the staffroom. “I expect all teachers to join us on Wednesday in our maandamano against the government.”

Had I known that was what he intended to say, I would never have let him speak. A few teachers nodded politely, but not one committed to joining him.

He also asked to address the students, but I firmly declined. Much as I wanted to see the students participate in civic action, I also cherished my TSC job. Later, I heard that Elkana had gone ahead and addressed students outside the school fence. I was just glad it happened off school grounds.

Wednesday: The Great Awakening

On Wednesday morning, I planned to visit Bensouda (for completely professional reasons) but decided to stay home instead. Surely, nothing serious would happen. Mwisho wa Lami has no protest history. And with leaders like Tito and Elkana at the helm, what could possibly succeed?

So, I was surprised — shocked, even — when I started hearing shouts and singing around 11am. At first, I assumed it was just children playing. But when I stepped out, I found dozens of kids following Apostle Elkana and Tito, holding placards and whistling as they danced in the dusty village square.

Some of the slogans read: “End Police Tocha!” “Ruto Mast Go!” “One Term Only!”

But it wasn’t just children. Grown-ups were there too — some curious, some excited, others clearly just following the crowd. I joined them, as did others, and soon the march moved past the chief’s office, right by the police post. I held my breath as we passed the police. Surely someone would be teargassed. But nothing happened. The officers waved. Some even clapped.

By 12.30pm, we had reached Apostle Elkana’s church. There, Elkana, Tito, and a young man who sat KCPE in 2023 (but didn’t proceed anywhere), addressed us. They announced that we needed to march around the village to gather more people. And off we went again, this time arriving back with a larger crowd.

We returned to the church, but the atmosphere had changed. Loudspeakers were blasting music. A table had been set up, and a microphone placed prominently at the centre. At first, it was secular music — then suddenly gospel began playing as Elkana made his grand entrance. The danceable gospel music soon turned into worship songs. The maandamano had transformed into a crusade.

From Protest to Pulpit

The placards disappeared. Hands were raised. Worship songs echoed. Apostle Elkana, when he finally stood up to speak, briefly talked about police, then went into preaching the gospel. The Gospel of THOAG, the gospel of salvation, the gospel of giving, the gospel of tithing, the gospel of sadaka.

And within minutes, people were being asked to give sadaka.

By that point, most of us had forgotten what had brought us there in the first place. I gave the Sh100 I had in my pocket, only remembering that this was meant to be a protest after I had given the money.

Before dismissing us, Apostle Elkana invited everyone to attend church again on Sunday. It was a massive harvest for him. Even people from neighbouring villages had joined.

Later that evening, I saw the head of the Mwisho wa Lami police post — I don’t know if he is OCS or OCPD — leave Apostle Elkana home. From how he walked, he hadn’t left empty handed. I now understood why he had not interfered with us.

Even Tito, one of the stingiest men alive, was generous that day. He bought drinks for a few of us at Hitler’s that evening. His only complaint was that we shouldn’t be having the Gen Z commemorative protests every year.

“This thing must happen monthly — every 25th! Once a year is too far.”