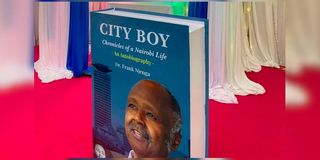

Dr Frank Njenga's new book, City Boy: Chronicles of a Nairobi Life—An Autobiography.

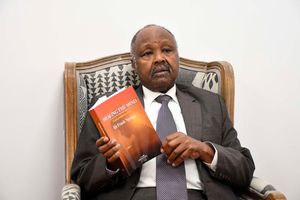

At the bottom left-hand side of the cover of the book, City Boy: Chronicles of a Nairobi Life—An Autobiography, by Dr Frank Njenga, there is a small, black and white photograph of him as a young man, swashbuckling, and with a beard in full riot—as defiant as an invading army. In the middle of the cover, there is a larger photograph of him, his face awash in the glow of the mellowing that comes with age, bald, with no beard but with a moustache with some grey hair.

In between the times these two photos were taken was a dream. A future like an unopened gift. That future could have turned this way or that. It is this future that is unveiled in City Boy: Chronicles of a Nairobi Life, Dr Njenga’s autobiography that was launched on Friday, March 9, 2025. His memoirs are also an ode to Nairobi as a first love, thus “city boy”—recreating the exuberance, the commotion, the promise, and the heartbreak of Kenya’s braying capital.

He reveals his life, warts and all. As an adolescent, he admits that he had his flaws: “In spite of the many warnings from my mother not to go looking for golf balls at the then 36-hole Royal Nairobi Golf Club, in what is now part of Ngumo and its surrounding estates, I did and nearly died on two occasions”.

And there is a lot of humour. I laughed aloud several times as I read. On their first trip to Mombasa with his brother, they were picked from the railway station by a Mr Kihara, who “had a covered pickup truck, and huge pieces of fresh meat hung from its ceiling. Our first journey in Mombasa as adolescents was punctuated by trying to dodge huge chunks of beef, which came at our faces at every turn…We alighted from the pickup in a somewhat dazed state”.

He has many personal vignettes. He liked keeping a long beard though it sometimes landed him in trouble. He says that the revered cop, Patrick Shaw, “lifted me off my feet at the National Theatre, mistaking me for a troublemaker because of my untidy beard”. His wife put a stop to these shenanigans. He writes, “…I met the girl I would marry. She, however, did not like my beard… she bought me an electric razor. Like Samson (with his hair), I drew all my strength … from my beard. This girl, like Delilah, wanted to sacrifice me to the Philistines”. After an agonizing period, he gave up his beard— for good.

And being a psychiatrist, he gives some practical advice. He narrates a sad story of a boy (his classmate) named Macharia Dan who didn’t understand anything the teachers taught in class. He would be caned by teachers until he had swellings at the back of his legs, but his grades still didn’t improve. The children bullied him, singing songs to shame him: “We would all point at him at the end of the song, and he would cry. I wonder how many children suffer this fate due to this and other medical conditions… He left school never to return… when I see young people in the streets, I see my classmate in them and wonder what might have become of his future if he had received the help he needed”.

There are many benefits of memoirs to society. First, memoirs allow us to see a different perspective, teaching us compassion and empathy. For instance, in a moving story, Dr Njenga captures a poignant story when he and Prof Githu Muigai had a moment with the late President Mwai Kibaki: “We both knew the retired President well, and our conversation was easy and pleasant… Just before we left, Githu asked about a famous May 1963 photograph in which he and Tom Mboya shared a bear hug as Jomo Kenyatta looked on... Then, unexpectedly, the former President began to cry… uncontrollable sobbing. We were shaken… why was he crying now? … He did not say”. But we can empathise.

Second, memoirs can help one grow as a person. For instance, one reading Dr Njenga’s memoirs gleans a lot of scientific insights on the functioning of the brains of teenagers and this could help parents and teachers understand teenagers better.

Third, memoirs have historical value and Dr Njenga’s memoirs are especially packed with history. He juxtaposes his life alongside that of Kenya as a nation, writing that, “Just as I struggled with the psychological, physiological, and emotional challenges of adolescence, Kenya was struggling to come to terms with herself… the young country, like my body, seemed at war with itself”.

We learn about the Mau Mau war of independence and about important national leaders and events, about the history of the Nairobi Arboretum and even about avenues and buildings. He writes, for instance, about, “…Khoja Mosque, established in 1922… Jevanjee Gardens, gifted to the people of Nairobi by A.M Jevanjee, an Indian-born businessman, in 1906… Sixth Avenue (later Delamere Avenue and today’s Kenyatta Avenue) … Whitehouse Road is (now) called Haile Selassie Avenue”.

There have been many autobiographies written recently in Kenya, but Dr Njenga’s is one of the finest to come from Kenya’s finest psychiatrist. Kudos, Doc!

The writer is a book publisher based in Nairobi. [email protected]