Renowned author Prof Ngugi wa Thiongo gestures during an interview with the Nation on February 7, 2019.

When the Kenyatta government stopped the staging of Ngugi wa Thiongo's play, Ngaahika Ndeenda, on November 27, 1977, it elevated him from a radical university of Nairobi don to a global figure.

A month later, his detention without trial would catapult him to stardom.

Of all his works, this play is better known—though in academic circles, his argument about language as a colonising tool has made him a must-read in postcolonial pedagogy.

How Ngaahika Ndenda shaped Ngugi's career is a story of a daring literature don who tested Kenyatta's presidency at a period that its secret police, the Special Branch, and attitude on negative criticism frightened most people.

The play that roared

Kamirithu, an open-air community theatre, offered Ngugi a stage on which he would launch his people-based campaign against the neo-colonial forces that had upstaged the proletariats in sharing the "matunda ya Uhuru"— as Ngugi's character would put it.

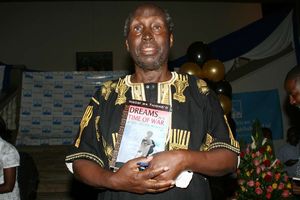

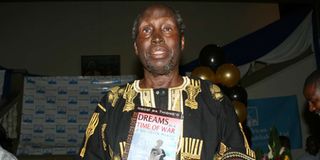

Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o holds a copy of his autobiography titled 'Dreams in a Time of War, after it was launched on August 19, 2010 in Nairobi.

Every Sunday, thousands of people would drive and trek to Kamirithu to watch the play— much to the chagrin of the provincial administration under Simeon Nyachae.

The Kamirithu Community Centre, which had been build by the locals, was turning into an arena of protest against betrayal by capitalists. It was also defining the Kenya's class struggle and relating that to every person's daily life.

Detained under the Public Security Act, the writer did not easily find global support. The US, which would have led in protest, was easy on Jomo Kenyatta and still treated Kenya's human rights record as "good". They still viewed Ngugi's detention as provided for in the Constitution.

As their ambassador Wilbert J. Lemelle wrote after Ngugi's detention, the embassy was in "doubt that raising the Ngugi affair further with the GoK would achieve anything for Ngugi…Kenyan courts cannot question the necessity of detention itself, although they can assure compliance with certain procedural rights."

The embassy appears tohave left the matter to Jomo Kenyatta's government: "It is impossible to estimate length of Ngugi's detention, but it seems this would be purely political rather than legal decision. It should be remembered that Ngugi was detained on express order from President Kenyatta upon alleged recommendation of Attorney-General (Charles Njonjo)."

There are no records on the US government, under Jimmy Carter, pressurising Kenyatta to release Ngugi.

First, Ngugi was seen through the Marxist debates that had taken shape and the US viewed Marxists and as anti-capitalism.

Thus, there was little sympathy on a Marxist – or Socialist in jail.

They said: "As we have reported in past, Kenya's human rights record is good, although not perfect. Attorney-General Charles Njonjo is conservative, authoritarian and strong advocate of law and order. On several occasions before Parliament, he has defended use of Public Security Act as necessary to deal with what he terms 'subversives'."

In Africa, in the 1970s, ‘subversives’ was the buzzword for communists, socialists and Marxists and they received little sympathy from Washington DC. However, though Carter was pragmatic, he still viewed Marxist-Leninists as dictators.

For Ngugi, he had a complex relationship with Marxist ideology throughout his career. Although he engaged with Marxist concepts and ideas in his writings and political activism, his views on Marxism— shaped by his experiences, context, and personal beliefs— have developed over time.

Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thiong'o. PHOTO| TIM WANYONYI | FILE

Initially, when staging Ngaahika Ndenda, he used that concept as tool for analysing and critiquing colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism, which were central themes in his literary works such as "Petals of Blood" and "Devil on the Cross."

That was before he made a shift towards cultural nationalism and started advocating for the decolonisation of the African mind and the revitalisation of indigenous languages, cultures, and knowledge systems.

It is this resistance that has shaped Ngugi's career in exile. His book, “Decolonising the Mind”, marked Ngugi's detour.

From then, he told the world, his works would be in Gikuyu language, first. Though he penned some works in Gikuyu language, and addressed international conferences with the same, he still continued to write some literary works in English.

By going into exile, Ngugi felt abandoned by the University of Nairobi, which he thought would become his ideological base, especially in the volatile 70s when universities were sites of academic freedom.

His detention and failure by the university to defend him brought some fear within academic circles. The US Embassy noted this in a cable: "There have been some rumblings at University (of Nairobi) and a deepening feeling of frustrations among intellectuals over the failure of the university authorities even to raise the issue of Ngugi's detention publicly."

Indeed, the literature don, novelist and playwright was on his own. How Ngugi got into Kamirithu is one of those stories that show how he took advantage of an emerging situation.

Kamirithu was a colonial village where thousands of residents had been bundled together in a mini-concentration camp during the crackdown on Mau Mau freedom fighters.

For a long time, a vacant building on a four-acre plot still stood in the village, and locals, led by Mrs Mary Waithanji, had, by 1976, turned it into an adult education centre. Here, the villagers from all walks of life attended evening classes. From June 1976 to July 1977, the first batch of 50-plus men and women could read and write.

After that, they engaged the best-known scholar from the village, Ngugi wa Thiong'o, to write a play for them that could capture their predicament.

The East African Literature Bureau, which had published Ngugi's “This Time Tomorrow” in 1971, had given an advance royalty payment of Sh200,000 while the balance for the construction of the centre was borrowed from various people— in the hope that they could be repaid from the gate tickets. After that, the name of the building was changed from Kamirithu Youth Centre to Kamirithu Community Educational and Cultural Centre.

Kenyatta's clampdown

The play, co-authored by Ngugi wa Mirii, a research assistant at the University of Nairobi's Institute of Development Studies, had elicited interest in Central Kenya, making many of the elites within the Kenyatta government uncomfortable. It was an indictment of the Kenyatta state and how it had handled wealth distribution. It was a hit – even among literary critics.

"Looking at the audience and actors, it is obvious they are enjoying themselves immensely and this not only goes to show that it is not only city slickers who enjoy drama but that drama has remained a part of African life," wrote Fibi Munene, a theatre critic.

The director of the play, Kimani Gecau, had told the Press that the team had worked with the community to stage the play.

Prof Ngugi wa Thiongo during an interview on February 7, 2019. He was recently interviewed by ‘The Guardian’ newspaper.

Gecau would later flee the country to exile— as part of the pro-Ngugi group that was pushed to exile. Another who followed Ngugi was his co-author in the “Trial for Dedan Kimathi”, Micere Mugo.

Although the play was in Gikuyu language, it started drawing large audiences from non-Gikuyu speakers and groups of high school students.

Then one morning, the local district officer, with instructions from Simeon Nyachae, then Provincial Commissioner, ordered the play to be stopped "until a fresh permit was issued." The permit never came.

Nyachae was policing the Central Kenya literary scene for any anti-government plays and music. He had not only banned political songs but never spared gospel songs with a political slant.

Ngugi's personal battles

In his autobiography, Nyachae wrote: "There was a lot of bitterness at the time in Central Province and indeed a song 'Maai ni maruru' (the water is bitter) was composed. It clearly portrayed bitter feelings about the murder of JM [Kariuki]. The song implied the government, which was supposed to protect them, had turned bitter against them. To contain the situation, I used my official position then to invoke the Chief's Authority Act to ban the song."

The song was by the Presbyterian Church choir, led by the late Ishamel Nganga.

Nyachae was still at the helm when Ngaahika Ndeenda emerged and used the provincial administration to silence the play.

But that did not end there. On December 31, 1977, Ngugi was picked up from his rural home and was detained without trial— triggering uproar from the international community and was adopted by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience.

Under the Public Security Act, under which Ngugi was detained, he was to be informed within five days the reasons for his arrest and there was no requirement to charge a detainee in court.

Even though their cases could be reviewed by a Special Tribunal appointed by the president and sitting in camera, the recommendations were not binding on the Head of State. The Kenyan courts could also not question the necessity of the detention, and that left detainees at the mercy of the Executive.

It was the harassment that he underwent and that of his family that would disengage Ngugi later on. On December 12, 1978, President Moi announced the release of all detainees. Ngugi was driven from Kamiti Maximum Prison to his house that night.

"Democracy is not praise-singing. Democracy is open talking and criticism. This eliminates disunity and leads to the solution of problems. It creates a good atmosphere and unity in the country," Ngugi told the Press.

But the detention had also wasted Ngugi. He started drinking and would get arrested by Tigoni police at the slightest provocation.

His marriage to Nyambura collapsed, and without a chance of ever getting his job back at the University of Nairobi, he left for Europe.

Later, he relocated the children to the US and left Nyambura in Kenya. It is this part of Ngugi that was later captured by his son, Prof Mukoma wa Ngugi, who recounted that Ngugi was violent towards Nyambura. This revelation of Ngugi as an abusive man revealed his other character – hitherto unknown.

But his detention produced yet another epic work, “Detained: A Writers Prison Diary” and his first Kikuyu novel “Caaitani Mutharaba-ini” (Devil on the Cross).

Mr Ngugi Wa Thiongo

The government was also keen to erase Ngugi's legacy in Central Kenya and in 1979, Kamirithu was razed down by the new Central Province Commissioner David Musila.

"As a new PC, I took it as my duty to engage the people and see if we could reach an agreement on the way forward. I held consultations with the local leaders and we decided the best way forward was to build an educational facility on the very spot where the open-air theatre once stood. I held a public meeting in the area and made an offer on behalf of the government to build a polytechnic for the benefit of the local youth," Musila writes in his autobiography. Musila would later invite President Moi to open the polytechnic – thus sealing the fate of Kamirithu theatre.

Abroad, Ngugi has taught at several universities throughout his academic career. They include teaching postcolonial studies at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. He also held teaching positions at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, where he taught courses on African literature, postcolonial theory, and creative writing. He later joined New York University as an English and Comparative Literature professor at NYU's Department of English.

His final position was at the University of California, Irvine, where he was a professor in the Department of Comparative Literature. Here, he taught African literature, world literature, and literary theory.

Also read the first installment in this series --> Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Life and Times

Also check this out --> 5 things you should know about Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o