The mothers left behind: Fight for survival as US aid cuts demand urgent lifesaving action

Mwaka Chimera holds her one-week-old baby. She received maternal health-care services through a now-terminated program, funded by USAid.

What you need to know:

- Stawisha Pwani empowered women’s health in coastal Kenya—its sudden halt risks undoing vital progress.

- USAid freeze disrupts reproductive care, forcing local governments to scramble for solutions and funding.

- Kenya received more than 60 per cent of its aid for family planning and reproductive healthcare from the US.

Published in partnership with the Fuller Project a non-profit newsroom dedicated to the coverage of women’s issues around the world.

Mwaka Chimera sits on a worn-out leather couch outside her two-roomed house in Vyongwani village, in south-eastern Kenya, cradling her new-born daughter.

“I dropped out of primary school, and for my first five pregnancies, I never attended a single antenatal clinic. I would just show up at the hospital when it was time to give birth,” Chimera, 31, says in Swahili.

“The difference in how I’ve cared for my last two children is remarkable, all thanks to what I learned in the group.”

Through her local mother-to-mother support group, Chimera says she’s learned the importance of prenatal check-ups and key screenings, including HIV testing. The group was part of Stawisha Pwani, a $47-million project that began in 2021 and was due to be completed in June 2026, but came to an abrupt end when, in January, the US State Department announced it would be stopping all but a small percentage of projects funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAid).

According to data provided to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), Stawisha Pwani was delivered by LVCT Health, a Kenyan non-profit that implements health programs, in partnership with local governments. Its mobile clinics, doorstep care for mothers in remote areas, and life-saving medicines have transformed access to health services in the coastal counties of Kwale, Mombasa, Kilifi and Taita Taveta in southeast Kenya.

“The program has truly transformed lives in this village,” she says as she gently rocks her baby. “I only wish it could continue – for the mothers who still need this support, for the babies yet to be born.”

$9.2 million of the original project budget is left unspent.

Community health promoters at a meeting in Kwale County. They discuss their future following the withdrawal of funding from the US.

Read more: Africa must act now for mothers’ survival

To get a sense of the global impact of the aid freeze, The Fuller Project analysed data submitted by donor countries to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and focused on four key sectors that disproportionately affect women: reproductive health, including pre- and postnatal care, delivery, infertility treatment and post-abortion care; family planning, including the provision of contraceptives, counselling and education; ending violence against women and girls; and supporting women’s rights organisations, movements and institutions. Reporters then combed through IATI data to identify specific programs, like Stawisha Pwani.

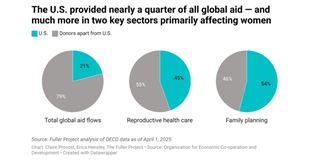

The data revealed that, while the US has long been the largest donor of foreign assistance – contributing just over one-fifth of the world’s aid in 2023 – its commitment varies by sector and region.

The US contributed more than half – 54 per cent – of the foreign assistance provided by all countries for family planning and 45 per cent of the total for reproductive health care in 2023, the last year for which figures are available, according to a Fuller Project analysis. In the same year, 26 countries received more than half of their family-planning aid from the US – 19 of them are in Africa.

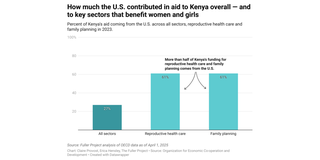

Kenya itself received approximately 27 per cent of all its aid from the US, including more than 60 per cent of its family planning and reproductive health care funding. Since the aid freeze, local health officials have been scrambling to continue to offer what services they can.

“As part of our immediate plans, we have requested approvals [from the local assembly] to absorb half of [approximately] 122 members of staff from the Stawisha Pwani project onto our payroll to ensure project continuity,” says Peter Mwarogo, health executive in Kilifi, one of the counties where Stawisha Pwani was implemented.

Against the backdrop of calls for Africa to seize this opportunity to rethink its reliance on aid, the Government of Kenya says it needs $522.16 million to sustain primary healthcare, procure essential medicines, and cover the funding gap left by USAid’s withdrawal. The Treasury is set to present its 2026 budget in April.

“We are reviewing current budget allocations to ensure that essential services in health, education, governance, and food security remain a priority,” Treasury Minister, John Mbadi, told parliament in March.

In the meantime, global health experts warn about the damage the stop-work order will cause, both to individuals and to health systems.

“Unfortunately, the fallout from these funding cuts will hit women the hardest, as they make up the majority of primary healthcare consumers, not just in Kenya, but across Africa,” says Dr Stella Bosire, executive director of the Africa Centre for Health Systems and Gender Justice.

“Funding cuts don't just disrupt reproductive health; they unravel entire healthcare systems,” Bosire adds. “These policy shifts widen funding gaps, putting millions at risk of losing access to essential healthcare services and jeopardizing vital work that has taken years to build.”

Her words are echoed by Evelyne Opondo, Africa Director at the International Centre for Research on Women.

“The progress we've fought so hard for is now at risk,” Evelyne says. “Urgent action is needed to safeguard the lives of women and children, who will be the hardest hit by the ripple effects of USAid funding cuts."

Musa Omar Mlamba, a community health promoter says no one has told them whether they'll be retained or if they’ll even be paid.

Back in Vyongwani, Musa Omar Mlamba, one of only two male ‘community health promoters’ at Vyongwani Health Centre, is deep in preparation for the next bi-monthly training with his group of 15 women.

“This session will focus on child nutrition, best breastfeeding practices, and maternal health. I’ll emphasize the importance of eating five balanced meals a day to ensure enough milk production,” he explains.

In a field dominated by women, he stands out – not just for his gender but for the trust and connection he has built with the mothers he serves.

“Empathy is everything in this job. My support group is thriving [because] I listen and I show up for them when they need me,” he says with pride.

But uncertain times lie ahead. For now, Mlamba has been able to continue working because he was on Kwale County’s payroll before the Stawisha Pwani program began. He hopes the county will still provide monthly stipends as before, but with Kenya’s health care system likely to be hardest hit by USAid cuts, as reported in February, it’s impossible to say how secure his employment is.

“No one has told us whether we’ll be retained or if we’ll even be paid,” he says. “With my children in school, I genuinely don’t know what to do. Who will support those who have dedicated themselves to supporting others?”

Methodology

Data analysis for this story relied on two primary sources of information on US and international aid spending: the The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Creditor Reporting System database and data published by donors to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI).

OECD data (accessible via the OECD’s Data Explorer) was used to put in context the U.S. contribution to total aid and for sectors that disproportionately affect women and girls. This data was extracted in constant (inflation-adjusted) prices to be able to look at aid over time.

IATI project-level data (accessible via the d-portal.org website) was used to identify specific projects, within these sectors, likely to be affected by the US aid freeze.