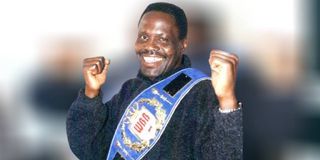

Former World Boxing Board heavyweight title holder Joseph Akhasamba takes a pose at his home in Emasatsi village in Kakamega County on March 23, 2022.

Kenya has produced many talented boxers over the years but it is the successful era of the famous "Hit Squad" boxing team that danced with the superpowers of the sport in the world.

Among these Kenyan boxers of the long-gone golden generation is Joseph Mukungu Akhasamba.

Now 63, Akhasamba represented Kenya at two consecutive Olympic Games -- Seoul 1988 and Barcelona 1992, losing in the quarter-finals, on both occasions fighting as a light heavyweight and heavyweight respectively.

Akhasamba won a gold medal for Kenya in the men's light heavyweight division (81Kg) at the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, New Zealand, and heavyweight silver at the 1991 All Africa Games in Cairo.

Kenya’s Joseph Akhasamba displays his World Boxing Board heavyweight title belt after defeating holder Rene Hanl on points in 2000. Behind his is veteran boxing official Reuben Ndolo. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

The idea of turning professional had not crossed his mind until he turned 32 and was informed of a decision by the International Boxing Association (Aiba) prohibiting anybody over 34 years from taking part in amateur boxing.

Aiba revised the rule in April 2013 raising the age limit for boxers taking part in the Olympics from 34 to 40.

This writer held a number of discussions with Akhasamba, mostly on the phone, to understand his early life, boxing career, the current state of boxing in Kenya and why boxers should learn to be self-reliant.

The legendary punching power of Akhasamba compared well with that of Arnie Shavers, the American heavyweight boxing contender during Muhammad Ali and Larry Holmes' reign as world boxing champions.

Shavers fought both and they admitted they had never been hit harder before.

Shavers is regarded as one of the hardest punchers in the history of boxing.

Just like Shavers Akhasamba stands at 6 feet tall and has an Orthodox stance.

In 29 professional fights, Akhasamba won 16, lost nine and drew one. It was a great effort against many odds.

Former World Boxing Board heavyweight title holder Joseph Akhasamba.

Except for a few fights where a promoter or manager would give adequate support, many were times when Akhasamba was left struggling alone especially when preparing for a fight and could not afford money to pay for a trainer and a sparring partner.

It is the responsibility of a professional boxer to pay for the services of a trainer and a sparring partner.

His first professional fight was against Abdul Kadu of Uganda at City Hall, Nairobi on October 1, 1994. He knocked out the Ugandan in the first of their scheduled four-round bout to earn Sh10,000.

His second fight earned him Sh7,000 while the third fight of six rounds earned him Sh6,000..

He had a series of successful fights against his fellow Kenyans including Paul Otewa who he knocked out in round three.

His real test came when he met a strongly built Thomas "Black Rhino" Okusi in an eight-round fight at City Hall in 1999.

Hard-punching Akhasamba knocked out the Rhino in round three to show his immense power.

The next fight, the same year, was against Christopher Sirengo who gave him a tougher fight than he had anticipated.

The two traded blows standing toe-to-toe for 10 gruelling rounds at Nyayo Stadium gymnasium before Akhasamba was declared the winner on points.

His win so impressed the Kenya Professional Boxing Commission (KPBC ) that he was given a chance to fight for the African heavyweight title against Emmanuel Chukwa of Nigeria.

The fight was staged in Nairobi on September 26, 1999, where Akhasamba won in the fifth round via a technical knock-out. That victory opened the way for Akhasamba to challenge for the World Boxing Board (WBB) belt.

Akhasamba got a Danish-based manager who organised for the WBB title fight against holder, Rene Hani of Germany.

The 12-round fight held in May 2000 in Dresden, Germany, and which Akhasamba won on points, earned him $10,000 in prize money and the WBB heavyweight title, becoming the first and only Kenyan to have owned a world title in that division.

He lost the title on his first defence on September 14, 2001, to German Willi Fischer at Offenbach, Germany on points. As a defending champion, Akhasamba was paid $15,000.

Asked whether he had a nickname associated with many of the boxers like Peter Kamau "Pipino" Wanyoike, John "Duran" Wanjau and Ibrahim "Surf" Bilali among others, Akhasamba says: "Yes, my boxing colleagues and fans used to call me ‘Nyundo’. I had a lot of punching power that gave me an opportunity to fight against heavyweight boxers and beat them even when I was a light-heavyweight. While I never underrated any of my opponents, I feared nobody when it came to boxing".

Akhasamba had no idea he would become a boxer as he grew up in Khwisero East in Kakamega County after his parents relocated to their rural home soon after his birth in Nairobi in June 1962.

His father had just retired and struggled to support his family.

Akhasamba dropped out of Eshinutsa Secondary School in Khwisero while in Form Two as his father could not afford school fees. He joined his elder brother Benson Namtenda, in Nairobi, in December 1981.

Says Akhasamba: "Even with no papers to show the level of my education, with a national identification card (ID) which I had acquired while in secondary school, I had high hopes of getting a good job in Nairobi. I found things were not as I had expected them to be. When I went to the industrial Area to look for employment, I only got casual jobs of loading goods into lorries."

One time he was hired to load iron rods for construction. He quit the job after being there for only two days on realising the materials were too heavy for him.

Life at Gorofani where they lived, between Majengo and Gikomba, was not easy either.

There were many goons who harassed him a lot whenever they met in the estate. He would soon come to learn that the gang members had a lot of respect for boys who had either boxing or karate skills. Akhasamba chose to learn boxing and joined Pumwani Boxing Club in May 1982 with the sole purpose of learning the sport to defend himself.

When he told the coach, Alex Omwomo, his reason for wanting to join the sport, he was told that boxing was not meant for street fights, but rather a sport that could get someone employment opportunities.

Kenyan heavyweight boxer Joseph Akhasamba displays the World Boxing Board Heavyweight belt he won in 2000 after beating German boxer Rene Hani in Dresden, Germany.

Says Akhasamba:"After training for three years, I took part in the 1985 national novice and intermediate championships and won in the light-heavyweight category. I also took part in that year's Kenya Open Championship and won in the same weight category. That marked the beginning of my career in boxing."

Circumstances have created heroes where the most unexpected happened. When Cassius Clay Jr.(later named Muhammad Ali) was 12 years old, his new bike was stolen from where he had parked it. Crying and with a lot of bitterness, he went to report to a nearby police station where a white policeman listened as Clay vowed to "Whup" that thief who stole his bike if he ever caught him. The police officer was Joe Martin who also ran a youth boxing club in Louisville, Kentucky. The policeman told young Clay that the only way he could "Whup" that thief was first to learn how to box. Clay joined Martin where he started training. The rest is history.

For Akhasamba, the initial idea of joining boxing to defend himself against Eastland's hooligans turned out to be a blessing in disguise as he excelled in the ring and got an opportunity to get a job at Kenya Breweries which had one of the best boxing clubs in Kenya. He worked for the company and also represented their club in tournaments for 12 years.

He says he was retrenched by Kenya Breweries in 1998 together with the majority of boxers and footballers but pro boxing came to his rescue.

On the current state of boxing in the country, Akhasamba says the lack of employment opportunities in both government and private sector is denying boxing clubs chances to tap talent.

“During our times, clubs used to have full teams covering all weight categories nurturing boxers from novice, intermediate and Kenya open,” he says.

He reckons counties should seriously invest in sports and help youth grow their talent and earn a livelihood.

Joseph Akhasamba (left) fights Mustapha Noor in an all-Kenyan pro event at Pal Pal gymnasium, Pumwani Social Hall, Nairobi, on November 13, 2008. He knocked out Noor in the second of their scheduled eight-round bout. PHOTO | FILE |

He plans to call get boxing coaches in Kakamega County together to meet the governor and discuss how to grow the sport in the region.

Boxing has enabled Akhasamba to live his life and support his family. He bought a piece of land to supplement the family land. He owns a posho mill he runs at his rural home and a few businesses he operates with his children in Nairobi.

His two last-born daughters are at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and Coast University respectively.

“You may have achieved a lot for your country winning medals and titles. But know, that when you exit the scene, the best that can happen is for you to be forgotten. Do not worry. Just continue with your life and do whatever you can to support yourself and your family. Those who want to recognise you will know where to look for you," Nyundo concludes the interview.