Raila Odinga and President Daniel arap Moi at Kasarani stadium during the Kanu-NDP merger.

Power-sharing arrangements in Kenya between ruling and opposition parties have now become a common practice since independence, with the latest being the “broad-based” cooperation that President William Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza administration has signed with former Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s ODM.

Other than power sharing, there have also been pacts crafted along the lines of coalitions, memorandum of understanding, alliances and cooperation agreements between rival parties, usually for the sharing of executive and legislative power.

Mr Odinga has been the architect of these arrangements from the Kanu administration of President Daniel arap Moi from 1998, followed by Mwai Kibaki in 2008, Uhuru Kenyatta in 2018 and now “the broad-based” government with President Ruto on March 7, 2025.

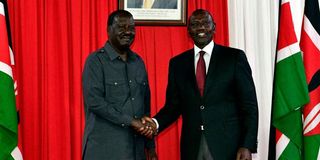

President William Ruto (right) shakes hands with ODM party leader Raila Odinga during the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between ODM and UDA at Kenyatta International Convention Center in Nairobi on March 07, 2025.

While many across the political divide have lauded such arrangements as critical in steadying the ship, others have blamed them for encouraging belligerence among even illegitimate contenders to power as a means of forceful negotiation with the legitimate contenders.

While eulogising Moi following his death on February 4, 2020, Mr Odinga revealed how his deal with the former president helped unite the country. This was after the two set aside their political differences, which included President Moi detaining Mr Odinga in the 1980s.

“Moi and I reconciled after the political differences of the 1980s and early 1990s and we were able to work together to bring more reforms in the country,” Mr Odinga said in 2020.

He added: “Our cooperation paved the way to the merger with his party Kanu (in 2002)”

Their cooperation, according to Mr Odinga, “put the country firmly on the path to a new constitution by enabling the formation of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission.”

However, Mr Barrack Muluka, a political analyst, said that such pacts are anchored on “selfish pursuit of power, control and that glory is at once the prompting, engine, fuel and driver of these power-sharing deals.”

“They usually come up when the regime in power is at its weakest and least popular. Hence, the outsiders see easy opportunities to tap into the flow of power, influence and wealth without bearing responsibility, should anything go wrong,” said Mr Muluka.

Mr Muluka notes that such arrangements unless “really needed”, defeat the purpose of the multiparty politics.

President Uhuru Kenyatta (left) and opposition leader Raila Odinga shake hands on March 9, 2018 in Nairobi. The handshake ended the acrimony that followed the 2017 presidential election.

Mr Odinga would later in 2008 find himself in government after he signed a grand coalition agreement with Mwai Kibaki, his main rival in the 2007 election to end the resultant post-election violence.

Before Mr Odinga came in, then Mwingi North MP and beaten Presidential candidate Kalonzo Musyoka had a deal with Mr Kibaki that saw him appointed Vice President.

In March 2018, Mr Odinga had a deal with then-President Kenyatta, who beat him in the 2017 presidential election.

The deal saw some of his ODM MPs elected to chair committees in the National Assembly hitherto headed by Kenyatta allied MPs because of their then numerical strength.

“It’s fishing in troubled waters. And it’s always been the same outsider! The same fisherman!” said Mr Muluka, a view shared by governance expert Barasa Nyukuri.

“Since the re-introduction of multi-party democracy in 1990, Kenyan politics has revolved around deals and MoUs between tribal kingpins in government and the opposition for the purpose of ascending to the country's leadership,” says Mr Nyukuri.

He is, however, quick to add that “these are short-term political arrangements that are driven by either the desire to win an election and form government or the fear of losing a general election to the opponents.”

“It is not illegal to have such pacts because we have pre-election and post-election power-sharing arrangements. But we should not abuse them for our selfish needs unless there is a crisis whose settlement requires such deals,” Mr Nyukuri says while making reference to the 2007 post-election violence.

Former President Mwai Kibaki and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga.

Prof Ben Sihanya, in his Power Sharing, Coalitions and Alliances in Kenya and Africa publication, notes that power sharing is “usually” achieved from three scenarios.

Prof Sihanya lists the three scenarios as the extra-constitutional power-sharing arrangements and coalition governments after civil conflicts, giving the examples of Zimbabwe and Kenya.

There are also the “consociational” power-sharing arrangements entrenched in the constitution and electoral system and the “consociational” power-sharing arrangements occasioned by “hung” Parliaments in Parliamentary systems.

He lists the cases of hung parliament as Germany, which had the grand coalition government under Chancellor Angela Merkel and Britain which had the coalition governments following the 2010 UK elections.

“The potential for political grid-lock is significant. Power-sharing governments are likely to stagnate in the short to medium-term,” says Prof Sihanya.

He notes: “This is because power-sharing arrangements are designed to make decision-making slow and consensus-based in order to re-assure parties that they will be consulted on matters of importance.”

According to Prof Sihanya, power-sharing pacts have been criticized for not aiding in solving the root causes of conflicts, but only postponing them until the power sharing arrangements run their course.

He reveals that this was the case with Rwanda, where combatants dissatisfied with the outcome of the 1993 Arusha Accord sabotaged the delicate peace-deal, “leading to the infamous Rwanda genocide that has remained the worst human catastrophe since World War Two.”

“Historically, the outbreak of civil wars in Angola, Cyprus, Lebanon, Sierra Leone, and Sudan have all been the results of broken power-sharing arrangements that led to renewed violence.”

University of Nairobi lecturer Herman Manyora argues that “one of the consequences of our current 2010 constitution is that it has imposed coalitions on us.”

“The rule that requires the winner of a presidential race to get fifty per cent plus one and also garner at least 25 per cent votes from at least half of the 47 counties, essentially means we are stuck with coalition politics,” says Mr Manyora.

This, Mr Manyora says, has been made more complicated “because of the ethnic architecture of our country and politics.”

The UoN don is basing his argument on the fact that before the current constitution, Kenyan politics has “always” been regional and ethnic.

At the dawn of independence in 1963, KANU and KADU, the two major parties, were organised around regions and tribes. The former, bringing together the Luo and the Kikuyu, with the latter bringing together the “so-called” small tribes.

“In the years that followed we have had cooperation, power sharing, handshake and now broad-based. It would appear that greed has been a major factor in all this. Greed for power and greed for money because reason alone cannot explain this political phenomenon,” argues Mr Manyora.

Former nominated Senator, Zipporah Kittony spoke on June 10, 2022, on how Jaramogi Oginga Oginga’s death scuttled the Moi power deal, “but Raila salvaged it.”

“I was privy to efforts by Raila’s father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, to cooperate with KANU. After the 1992 general elections, Jaramogi summoned all Luo MPs to a meeting where he expressed his intentions to work with President Moi,” says Ms Kittony.

She notes that Jaramogi felt that his exploits in politics had served- for the first time in Kenya history to push all Luo MPs to the opposition, and thus “he was looking for a way of ensuring the community was not left out of decision-making and sharing of the national pie.”

Ford-Kenya was Jaramogi’s political party that he used to secure the Bondo parliamentary seat. But that pact was not realised as the 82-year-old Jaramogi died on January 20, 1994.

Prime Minister Raila Odinga and former President Daniel Moi during a church service at AIC-Kabarak Community Chapel on July 8, 2012. Photo | REBECCA NDUKU | PMPS

According to Ms Kittony, Mr Odinga’s revitalisation of the National Development Party (NDP) in 1996 and his impressive performance in the 1997 presidential election presented an opportunity for him to engage the Moi administration.

The merger between Kanu and NDP was actualised on March 18, 2002, at a meeting of delegates of both parties at the Moi International Sports Centre, Kasarani, in Nairobi.

Mr Odinga replaced Joseph Kamotho as Secretary-General of KANU and the party’s vice-chairmanship positions.

Veteran Journalist and political commentator Salim Lone says that power sharing in government is a global phenomenon.

“We see everywhere the powerful and the rich gaining even greater power even within long-standing democracies. Our dependent societies find it hard to escape that vice, including in our domestic politics,” says Mr Lone.

This is even as Mr Lone argued that the crises afflicting Kenyans keep on intensifying and the system seems to be at breaking point repeatedly.

“We must also keep in mind that we have had long periods of seemingly impossible challenges, but we have produced popular reformist leaders who came together to win glorious victories through broad coalitions, as in 2002 then again in 2008 and 2013.”

“That is the key to our progress. Broad-based coalitions which bring together progressive popular leaders supported by their people. This can still happen,” says Mr Lone.