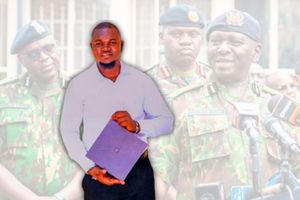

Teacher Albert Ojwang who mysteriously died in a police cell.

As public outrage boils — and as police chiefs and government officials shed their ritual crocodile tears over the chilling murder of blogger Albert Ojwang, Kenyans are forced to confront a grim, familiar truth; this is not new. It is but the latest entry in a long, blood-stained ledger of state-sanctioned disappearances, deaths in custody, and the dark craft of official cover-up.

In Ojwang’s case, the initial official explanation was that he committed suicide by repeatedly smashing his head against the walls of his police cell. It is a grotesque insult to public intelligence — a tale so transparently absurd that it exposes not only a contempt for truth but a staggering confidence in impunity.

Inspector General of Police Douglas Kanja addresses journalists on June 9, 2025 at Central Police Station over the death of Albert Ojwang (inset) in police custody.

We have long known that the history of police rot and cover-up runs deep. But this? This stretched the limits of disbelief—and in doing so, laid bare the brutal anatomy of a system that has long learned how to kill, deny, and move on.

It is a script we’ve seen before. People die. We are lied to. And nothing changes. History bears witness — not as a passive observer, but as an indictment of those who kill, conceal, and move on with impunity.

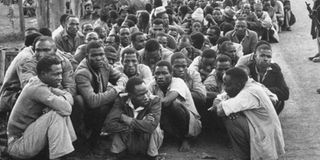

Let us start from the Hola massacre in the 1950s when colonial police killed 11 detainees by breaking their skulls and limbs. The official explanation was that they had died of drinking foul water!

Hola was a torture site masquerading as a “rehabilitation camp” for freedom fighters who dared to demand an end to white rule, land dispossession, and racial privilege. These detainees were not criminals—they were men who had envisioned a future in which Africans governed themselves. But to the British colonial establishment, they were not patriots but “savages,” “hardcore insurgents,” and “mental defectives”—labels used to justify their brutal repression and to sanitise the violence of empire.

To suppress the Mau Mau uprising, the British established detention camps — an archipelago of barbed wire, isolation, and forced labour that ultimately held more than 70,000 Kenyans without charge or trial. This was not justice. This was colonial fascism clothed in legal fiction. Within these camps, especially in places such as Hola, detainees were subjected to systematic beatings, starvation, humiliation, and back-breaking labour under the euphemism of “rehabilitation through work.”

Mau Mau suspects are rounded up in Kenya.

Then came the horror of March 3, 1959, and eleven Mau Mau detainees were beaten to death by colonial guards. Their “crime”? Refusing to participate in forced labour. The official British explanation? That they had died after drinking contaminated water.

What followed was not accountability, but a textbook colonial cover-up. The bodies bore the evidence: shattered skulls, ruptured organs, internal bleeding—injuries that no water could cause. Yet the colonial government doubled down. Files were sanitised. Reports were rewritten. The blame was pushed downward onto junior officers. The system that had orchestrated the killings sought to erase itself from the scene of the crime.

But the truth—fragile, contested, and nearly buried—refused to die. Thanks to the courage of a few journalists, whistleblowers, and backbenchers in the British Parliament, the story leaked. It exploded in London. The photographs, the inquest reports, the testimonies—all laid bare the empire’s moral rot. Hola forced the British public to confront the violence carried out in their name, under their flag, by their government. While this incident hastened the dismantling of the detention camp system and gave new fire to Kenya’s independence movement, it appears that police never learnt. In essence, the water wasn’t dirty — the system was.

What made Hola possible did not end in 1959. It mutated. Today, people still die in the custody of the state. Truth is still manipulated. Responsibility is still deferred. And power still behind silence.

In 1975, populist politician Josiah Mwangi Kariuki—fondly known as JM—walked out of Nairobi’s Hilton Hotel alongside police officer Ben Gethi. He was never seen alive again. The official story? That JM had travelled to Zambia. The truth? His tortured body was later found dumped in Ngong Forest, riddled with bullets, eyes gouged, and fingers missing.

The late politician Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki.

In Kenya, the line between law enforcement and lawlessness has always been faint—blurred further by a system that protects the executioners while punishing the whistleblowers. It is a system that hires shadowy figures to mete their own version of justice and get away with it.

In the 1970s and 80s, we bore witness to the reign of Patrick Shaw, a shadowy police reservist whose name became synonymous with extra-judicial executions. Shaw roamed Nairobi’s streets in civilian clothes, acting as judge, jury, and often, executioner. His legacy is one of bullets and blood—of suspects shot on sight, sometimes without proof, sometimes without cause.

On the day JM Kariuki was abducted, eyewitnesses claimed Shaw had cleared the area around the Hilton Hotel, warning taxi drivers and regulars to disperse. It was a quiet sweep, the kind that precedes a storm. Testimonies later revealed that Shaw had been tailing JM for days. According to Mr Macharia of Intrav Travel Agency — then based at the Hilton—Shaw followed him while he borrowed JM’s car, looping through city streets, right up to the Ambassadeur Hotel. The message was clear: the net was closing.

Behind the scenes, the state deployed a cast of criminals-turned-informants to do their dirty work. One of them was Peter Kinyanjui, alias "Mark Twist"— a man the parliamentary select committee investigating JM’s murder would describe as “a criminal of the worst possible character.” Yet this very man held meetings with the director of criminal investigations, Ignatius Nderi. Their mission? To entrap JM in a fake narrative linking him to the bombings that rocked Nairobi that year.

“This man [Kinyanjui] — though a criminal — was employed by the police to follow JM on that day,” the committee would later report. But by then, it was too late.

And what does that tell you? That police would always concoct narratives to cover up.

The late Robert Ouko. Photo/FILE

Nearly two decades later, in 1990, another high-profile figure—Cabinet minister Robert Ouko — would vanish under equally murky circumstances. The state said suicide. According to the then government pathologist Jason Kaviti, Ouko broke his own leg, undressed, set himself ablaze, and then shot himself in the head. Yes, in that order.

But British investigator John Troon, deployed by the Kenyan government under international pressure, wasn’t buying it. His forensic team quickly determined it was murder. Yet Troon's pursuit of the truth was met with brutal resistance. Witnesses were threatened. Some were assaulted. Ouko’s own brother was abducted by police mid-interview and returned hours later, battered and bruised with rubber truncheons. His crime? Telling the truth.

Thus, from Hola to JM, to Ouko, to Ojwang—the pattern is hauntingly familiar: state agents seize their targets, official lies follow, and truth becomes the first casualty. What remains is a grieving public, still waiting for justice, still haunted by the same question.

Perhaps we have reached a stage where crocodile tears will no longer silence our demand for truth. We now wait to see whether the Independent Policing Oversight Authority will rise to its mandate—or if, once again, it will be reduced to a smokescreen for impunity, deployed not to uphold justice but to manage outrage. We’ve seen the playbook before.

Until the day of reckoning arrives, the silence of the forest—Ngong, Karura, or otherwise—will echo with the names of those Kenya lost not to chance, but to design. It is the silence of a nation that kills, buries, and forgets—then rewrites the story to exonerate the perpetrators. But every lie leaves behind an unrested ghost. And one day, those ghosts will demand to be heard. Rest in Peace Ojwang.

Kamau is a PhD candidate at Department of History, University of Toronto, Canada. Email: [email protected] @Johnkamau1