Top row from left: Sylvester Opiyo, Ahmed Kariuki and Titus Kibett. (Middle row) Wycliffe Ovaga, Kariuki Mwangi and Hemed Salim. (Bottom row) Pius Wekesa, Molu Yatani Elle and Kuni Elle.

On February 2, 2014, a police raid on Masjid Musa mosque in Mombasa ended with seven people dead—including the mosque’s muezzin and a Rwandan national—and marked the last time anyone saw Hemed Salim.

A respected electrician and active member of the congregation, Hemed had gone that morning to install speakers for a religious event.

By nightfall, his wife, Sada Suleiman, watched the horror unfold on television.

“I saw him on the 7pm news. The police were raiding the mosque. I spotted him clearly. They said they had arrested him,” she said.

What followed was a descent into anguish. Ms Suleiman immediately contacted her brother-in-law, hoping they could trace Hemed’s whereabouts.

Police first admitted to arresting him alongside other terror suspects.

But while the others were loaded into a police lorry, Hemed was taken separately in a Land Cruiser.

Days later, the authorities claimed he had “escaped”.

Hemed Salim Ahmed (right) being arrested by police during the police raid on Masjid Musa Mosque in Mombasa on this photo taken on February 2, 2014.

Human rights groups, including Haki Africa and Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI), helped her search through police stations, hospitals, and morgues across Mombasa.

Still, there was no trace—no paper trail, no explanation, no closure.

“Our lives changed completely. I had to move in with my sister, who later died. Now I’m caring for her children and mine with no support,” she said.

Today, Hemed’s three children are adults, the youngest is 18, the eldest 26.

One dropped out of school due to financial strain.

“The authorities promised to help with the children. Those were just empty words. I just want the government to tell me where he is. If he’s dead, let me know so I can move on,” she said.

Hemed’s case is far from unique.

Enforced disappearances

According to Francis Auma, Emergency Response Officer at Muhuri, enforced disappearances have become entrenched in Kenya’s counterterrorism playbook adding that the cases have been around for over a decade, even in the previous regimes.

He linked the rise in abductions to Kenya’s military incursion into Somalia and retaliatory strikes by al-Shabaab.

Victims are often last seen in the company of plainclothes officers who claim they are taking them to the station. Families who follow up are met with silence or denial.

“Profiling is rampant. In the coastal region especially, anyone with a terror-related history, even if the case was cleared, is vulnerable,” he said.

A 2023 report titled “Gone but Not Forgotten: Unlawful Killings and Enforced Disappearances of Kenyan Muslims” by Haki Africa and the Justice Forum documented 82 such cases from 2012 to 2023.

The majority of the victims were Muslim, and many of the disappearances were linked to Kenya’s elite anti-terror units.

Despite the constitutional right to habeas corpus, not a single successful petition has compelled police to produce a missing person.

Mr Kamau Ngugi, the Executive Director of the Defenders Coalition, said this failure undermines trust in the judiciary.

This trend, he said, greatly gnaws at Kenyans’ confidence in the state, its officers and even the and they might resort to informal institutions and extrajudicial options to get justice.

“Even when there’s clear evidence, the State refuses to comply. It erodes public trust in the courts and forces people to seek informal justice,” he said.

Far from the coast, in Marsabit County, the scars are just as raw.

Amina Jarso was eight months pregnant in 2016 when her husband, Badar Umar, vanished. With a toddler already in her care, her life was turned upside down.

During the ethnic clashes that rocked Marsabit in 2022, the disappearances increased. Saku sub-county alone recorded over 20 cases.

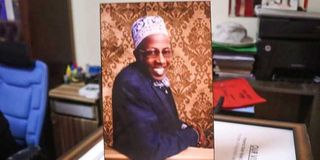

A portrait of Kuni Elle.

One case is that of Kuni Elle, a prominent Marsabit businessman who vanished during the violence. Soon after, his son, Molu Yattani Elle, was reportedly taken from his Nairobi home by men believed to be officers from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI).

Neither has been seen since.

In Nairobi’s Majengo area, Zena Wanjiku Ali still mourns her missing husband, Sylvester Opiyo—known in the community as Musa Osodo—who disappeared in 2012.

Sylvester Opiyo.

“He had faced terror-related charges but was never convicted. In 2012, he took three people, including a woman, a man named Jacob Musyoka, and a young girl to a madrassa in Kisumu. Before they arrived, police stopped them in Molo. Musa and his friend were pulled from the car and never seen again,” said Zena.

Years later, their children still struggle to get national ID cards or access higher education because their father’s status remains unresolved.

“How do you prove he’s dead without a death certificate? Our children are suffering,” she said.

In 2016, another Nairobi family lost their breadwinner. Muna Mohamed’s husband, Abdalla Iddi Waititu—known as “Duktur”—disappeared after leaving work at Kangundo Level Five Hospital.

He was last seen being approached by three men. He never returned.

At the time, Duktur was pursuing his PhD in Pharmacy.

His family searched hospitals, mortuaries, and police cells—nothing.

Soon after, his friend Karuri Mwangi, nicknamed Lovi, who had been questioning the police, also vanished.

“How could someone so well-known, who even vied for a county assembly seat in 2013, just vanish without a trace?” Muna asked.

To Sheikh Ali Shekuwe, Deputy Imam of Majengo Mosque, enforced disappearances are part of a broader campaign of fear.

Arbitrary arrests

“People here are used to arbitrary arrests. Some return. Some don’t. And when families ask questions, more disappear. This community lives in fear,” he said.

Among the cases he has documented is that of Ahmed Kariuki, 23, abducted on October 3, 2019 in Pangani, just weeks after being acquitted in court in Garissa.

He had recently bought a motorcycle to support himself. Witnesses say he was forced into a white vehicle. His motorbike was left behind.

Some victims live to tell their stories.

Lavani Mila, a youth leader and activist, was abducted in October 2024 after participating in the “Gen Z” protests.

“Those people, who I believe were police officers, kept asking who was funding the protests and beat me until I lost consciousness. I woke up dumped by a river,” he recalled.

Lavani believes his activism made him a target. After his release, he joined efforts to trace the “Mlolongo Four”—Martin Mwau, Kalani Muema, Steven Kavingo, and Justus Mutumwa—who were abducted in December 2024. Mwau and Mutumwa were later found dead at the Nairobi Funeral Home under suspicious circumstances.

Civil rights organisations filed a habeas corpus petition seeking the release of Kavingo and Muema. The case was dismissed by Justice Bahati Mwamuye, citing insufficient proof that the state had custody.

“This court concludes that the petitioners failed to prove the missing men are in the custody of the respondents,” the judge ruled.

Meanwhile, other families wait in silence.

Titus Kibett, alias Tito, disappeared on March 13, 2024, in Mlolongo, Machakos County. His wife, Norah Bett, said their search has yielded nothing.

Titus Kibett.

“It has been over a year. I have been in despair. The police have not helped in the search for my husband. He was peaceful. Please, I need to know if he is dead or alive,” she said.

In Kawangware, Pius Wekesa—a newspaper vendor—went missing on January 28, 2025. His son, Davis Wekesa, said his father never missed curfew.

“He never failed to be home by 7 p.m. We’ve searched everywhere. We just want to know if he is dead or alive,” he said.

Wycliff Ovaga

Elsewhere in Lavington, John Ambasa is still looking for his brother, Wycliff Ovaga, a caterer who vanished in December 2024 on his way to work. His motorbike also disappeared. His wife and children have since been displaced due to financial hardship.

“My brother was soft-spoken and always helpful. We’ve been to Kihara Police Station and DCI headquarters. We don’t know if he is dead or alive, but we want to find him,” Ambasa said.

A 2024 report by the State-funded Kenya National Commission on Human Rights revealed that security forces killed at least 63 people and injured over 600 during the Gen Z protests. Another 1,376 were arbitrarily arrested, and 74 forcibly disappeared. Twenty-six remain missing.