The fountain of knowledge at the University of Nairobi.

I have spent the last 44 years of my life in and around the University of Nairobi (UoN). I can claim, without apology, that if there is any institution in Kenya I know and understand, it is the UoN.

In recent times, our alma mater has resembled Samuel Beckett’s proverbial theatre of the absurd. Although some may argue that UoN activated a self-destruct mode (as they say in downtown Johannesburg), the bitter truth is that the current crisis is the culmination of a series of historical missteps. Many of these date back to the immediate post-independence era in Kenya, but most - at least in my considered view - peaked after the exit of President Daniel Moi in 2002.

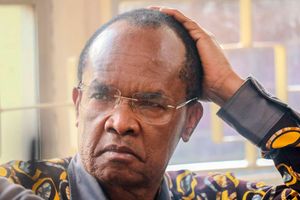

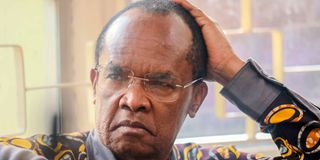

As I explain later in this article, an ever-mutating clique in our political establishment has, since time immemorial, believed that an institution like UoN must be led by a “gatekeeper” - not necessarily someone who knows anything serious about anything! As long as this thinking continues to shape leadership appointments at public universities, even if you remove Prof Amukowa Anangwe as Council Chair (as has already been done) and bring in Jesus Christ himself, the university is unlikely to recover soon.

Prof Amukowa Anangwe has resigned as University of Nairobi Council Chairman.

To truly save our public universities, we need bold and sweeping reforms. We must appoint well-tested managers who can work with academic leaders and thinkers. Time and space may not allow me to delve deeply into what these steps entail, but here’s the long and short of it: if the government continues to prioritise cronyism and blind loyalty as the unwritten criteria for appointments, expect nothing. That said, you could settle on a disruptive, innovative thinker who is, at the same time, loyal and conformist. We have quite a few such individuals in our academic ranks, though they have kept a low profile - many sidelined for not being politically correct.

Disruptive thinking is not anti-government; rather, it describes individuals who are innovative, gifted, and capable of generating fresh ideas that bring meaningful societal change. Cronyism, by contrast, rarely produces such individuals. Cronies are often satisfied with petty achievements, and for them, as long as their patron is pleased, institutional function can go to hell! This, I believe, has been the main bane facing UoN, and virtually all public universities in Kenya.

Much has been written about how the Jomo Kenyatta regime (1963-1978) ignored the well-prepared succession plans that the colonial establishment had laid out for higher education institutions in East Africa - Nairobi, Makerere, and Dar es Salaam. While Tanzania and Uganda ensured relatively smooth transitions to leaders who had been groomed for the roles, Kenya brazenly reneged, and we’ve never recovered from that misstep.

Researchers of that era note - truthfully, I believe - that the appointment of Dr Joseph Karanja as Vice-Chancellor, despite never having been an academic or staff member, signalled that UoN would not be run on scholarly or managerial merit. That attitude has never faded.

The late Joseph Karanja, who once served as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Nairobi.

Today, you may attempt to fool the public into believing that qualified individuals apply and go through competitive interviews, but we know uncomfortable inner truths. At UoN, the absurdity continues with the Public Service Commission (PSC) - a body whose independence and capacity to handle such tasks is highly questionable - conducting interviews for top university management positions.

I’ve stated in earlier opinion pieces that while Dr Karanja may have been a beneficiary of Mzee Kenyatta’s tribal hegemonic tendencies - trends that still plague much of Africa - he nonetheless managed to steer UoN onto a trajectory that defined its growth through the 1970s and 1980s. Since his departure, I cannot think of any Vice-Chancellor who has leveraged UoN’s fortunes to build a formidable university economy in and around Nairobi.

That opportunity remains a low-hanging fruit - one cronies will never see. Worse still, these cronies have co-opted questionable academics, shifting the focus from building a self-reliant institution to, you guessed it - eating! One day I’ll speak more candidly about the Universities Academic Staff Union, which we painfully founded in a different era, and what it has since become.

Questionable individuals

Let me briefly recall what UoN was like when I joined as a student in 1981, and later as a staff member in 1988. All you needed then was a staff ID, and you would be treated with dignity at both Nairobi and Aga Khan hospitals. The senior staff clinic functioned well, and most specialists were within easy reach. Many of us received accommodation in Nairobi’s better middle-class neighbourhoods. My own bachelor apartment in Kileleshwa came furnished - with a bed, bookshelves, cooker, and servant’s quarters for two. You could literally walk in with a briefcase and start work immediately. Before my apartment was ready, UoN even housed me for two months in one of Nairobi’s better hotels, as part of my relocation.

In such conditions, people with a scholarly calling had no hesitation in contributing to Kenya’s knowledge production enterprise. Our academic seniors inspired us with stories - like how, in the 1970s, a university professor could buy a brand-new car from a showroom based on their payslip alone. It is not a national secret that lecturers were once on par with senior civil servants. Today, when you flip through various WhatsApp groups for lecturers and professors, you might think you’re reading the Book of Lamentations.

What I’ve witnessed in my later years at UoN should alarm anyone who hopes for a quick fix. As the country slid into economic crisis, UoN - and later other public universities - began to attract questionable individuals. Politically appointed council chairs and members lowered standards, hiring academic staff with unverifiable backgrounds. Many joined UoN simply because they were jobless - not because they were driven by scholarship. I’ve watched as both undergraduate and postgraduate programmes admitted students who had no business being in a university environment.

But perhaps the greatest tragedy is that it’s the crony, politically correct group that launched the “tooth, nail, and pants” struggle (as Francis Imbuga would put it) to occupy the administrative university. Like everything they touch, even deserved academic promotions were sidelined in favour of choreographed cronyism. Independent scholars were blacklisted. This group, knowing little about universities, has contributed to institutional decline - especially by neglecting the need for a functional and conducive learning environment.

For the avoidance of libel, I will not name names - but they know themselves. This is the same group that gradually turned the Vice-Chancellor’s post into a quasi-ministerial appointment. When I joined UoN, VC Joseph Maina Mungai was a humble man who drove an old Volkswagen Beetle and occasionally walked into examination halls. By contrast, later VCs became demi-gods, flanked by armed guards and behaving like they were superintending lesser mortals. The excuse that Prof Joseph Nyasani’s isolated gunman incident necessitated such security should be tossed aside.

So, what can be done?

First, as stated above, identify a disruptive thinker who, while loyal, brings innovation.

Second, find a thoroughbred UoN person - someone who commands peer respect through scholarly achievement, with significant international exposure and verifiable networks to tap into.

The entrance to the University of Nairobi, main campus.

Third, if ethnic bigots continue to insist on gatekeepers, then restructure the entire system and hire track-record managers on short-term contracts to re-engineer the institutions.

As I’ve written elsewhere, Kenyan professors tend to be poor university managers, unless you find one who can think beyond their narrow specialisation, or one born with natural leadership attributes. In that regard, George Magoha had some of those qualities, which made him a memorable VC - more so than those who followed.

I know some of my views have ruffled feathers, but I welcome debate with peers who understand the value of new thinking. I’ve also argued that the VC’s post could be part-time, rotated among respected professors who advise and support a career manager handling the day-to-day operations.

Unless we consciously leave universities to scholars and competent managers, our huge investment in higher education will never yield returns or transform the nation.

Prof George Odera Outa is and interdisciplinary scholar, presently based at the Technical University of Kenya, having previously served at UoN for over 30 years