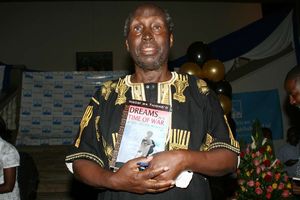

Celebrated Kenyan author and scholar Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

He opened his worldly book with the name James and closed it after long dropping the name. He arrived in the world in Kamiriithu, Limuru, Kenya; departed in Atlanta, United States. He shot into the scene while writing in English; departed while writing in Gikuyu.

That was Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o. With his death at the age of 87 on Wednesday, Kenya lost its best export in the world of literature. You will run out of fingers and toes if you use those to count the number of global accolades he received.

Numbering around 38, and issued in regions ranging from Kazakhstan to Hawaii, the awards showed that the world long noticed his potential—only that it wasn’t quite convinced to give him the coveted Nobel Prize for Literature to crown it all.

His works, written from the early 1960s, have been translated into more than 100 languages. Having done at least eight novels, three short story collections, five plays and five memoirs, his works have also been studied by millions in Kenya and elsewhere.

After his death, the latest cohort to study his 1965 novel “The River Between” was full of memories, lacing their condolence messages with various extracts from the book.

Ms Ronah Saada, who studied the book in secondary school, said she picked a lifelong lesson from it.

“From the novel, we learn to fight for independence,” she said. “(He also preaches) holding tenaciously to African culture that the colonial authorities endeavoured to erode.”

Prof Ngugi wa Thiongo during an interview on February 7, 2019. He was recently interviewed by ‘The Guardian’ newspaper.

Now, the literary titan has confronted death, a concept he romanticised in his 1976 novel “A Grain of Wheat”. The book was inspired by the Bible verse that says that unless a grain of wheat dies, it remains just one seed. If it dies, it grows into a plant that bears more.

His fruit was abundant even in life, though there are people who feel Kenya did not honour him enough. They include author Silas Nyanchwani and Dr Saisi Marasa, the founding president of the Kenya Diaspora Alliance-USA.

Said Mr Nyanchwani: “I just wish we celebrated him more back at home, honouring him with statues, monuments and even scholarships and prizes in his name. It will be a while before we can have a thinker of global repute.

“He was big in ways we haven’t appreciated [yet]. I have met people from India, South Africa, all over the world who know him and love his work. Our government and institutions failed to honour him in a befitting way.”

Dr Marasa argued: “It’s a shame successive Kenyan governments never recognised this great son of Kenya, but his works will never die. They live on in our hearts.”

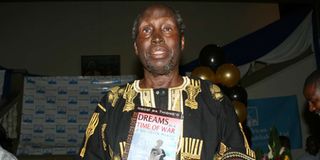

Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o holds a copy of his autobiography titled 'Dreams in a Time of War, after it was launched on August 19, 2010 in Nairobi.

He shared a video he recorded in June last year when his diaspora group held an event to honour the ageing scribe. In it, Ngugi is seen dancing as he smiles, supporting himself with a metallic staff.

The age in his bones showed. His kidney and heart problems were definitely slowing him down. As was typical of him, he was dressed in a flowing robe—after his transformation that saw him drop his English name, he also grew a taste for clothes with a more African philosophy.

“We are glad we gave Mzee the roses while he could smell them,” said Dr Marasa. “It’s a sad time we lost a legendary literary icon and social justice defender who never minced words whenever he identified violations of human rights and injustice in government.”

Writer Carey Baraka, who interviewed Ngugi for an article published by The Guardian in 2023, told the Nation that the novelist’s death “made me sad”.

Mr Kiarie Kamau, the CEO of the East African Educational Publishers (EAEP) and the chairperson of the Kenya Publishers Association, said Ngugi had a talent many authors lack.

“Ngugi stood out for his literary versatility. Few, if any authors, have been able to master virtually all literary genres, and produce award-winning works: novels, short stories, poetry, essays and even children’s literature,” he said.

“For EAEP, he was not just an author. He was part of the corporate family, having joined it way back in the early 1960s when he published his first novel ‘Weep Not, Child’.

Throughout his journey with EAEP, he authored works that have received global acclaim, with his latest, ‘The Perfect Nine’ (Kenda Muiyuru), attracting translation requests into major work languages,” added Mr Kiarie.

For Prof Peter Amuka, who was a student of Ngugi’s at the University of Nairobi (UoN) in the 1970s, there were many fond memories to share.

“When I and a first year classmate first saw Ngugi at the foyer of the [UoN] Education Building, we were surprised at his height. We had assumed he was a giant the size of Okot p’Bitek. But my friend quickly observed that the novel ‘A Grain of Wheat’, made him much taller,” he said.

Prof Amuka, who has been a teacher of literature at Moi University, recalls being sad that he could not be taught by Ngugi until his second year of his studies.

“We couldn’t wait to meet him because some of us had expected to be taught and inspired by his teaching and mentorship to become writers,” he said. “Yet you couldn’t miss Ngugi even if he didn’t teach you.

He was all over the campus in seminars, writers’ workshops, along the corridors and the media. Ngugi the person and teacher I met in and out of the classroom between 1973 and 1977 can only be described as very kind and passionate about knowledge and its social significance and purpose in Kenya and beyond.”

Prof Amuka recalled that Ngugi was a generous lecturer who would come to the assistance of students often. He would be a common feature in students’ strikes.

“On such occasions, we would be sent home and Ngugi was always willing to offer fare to some of us,” recalled Prof Amuka.

“Many times, he would request a student to fill his name on a bank cheque and pick cash from Barclays Bank, Market Branch, for him. It was always Sh150 daily. On returning to his office, the student would be routinely given Sh50. That was a lot of money those days. I benefited many times.”

However, Ngugi didn’t stay too long as a lecturer before troubles began with the government, which saw him flee to exile.

In 1962, Ngugi submitted his first manuscript to a publisher. He told the Sunday Nation in 2008 that it was a collection of short stories, and that it was rejected. In 1971, the world got to know that he had dropped his first name “James”.

A critique of his work “This Time Tomorrow” in the Sunday Nation of May 16, 1971 noted: “He has changed his name to Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. In [one] photograph, he had discarded the ancient English woollen pullover for a kitenge shirt.”

Ngugi was known to encourage other people to drop their “English” names, including Mr Baraka. Nation journalist Marion Wanjiku said she changed her writing name and Facebook name to “Wanjiku wa Maina” after a 2019 encounter with Ngugi.

He was detained by Jomo Kenyatta’s government at Kamiti Maximum Prison for a year before he was released. His time under the government of President Daniel Moi was also not smooth and he chose to head to self-exile.

While in exile, Prof Ngugi married Njeeri. He had been married to Nyambura, who was at some point a freelance photographer with the Taifa Leo newspaper.

When he spoke with The Guardian in the interview published in 2023, he revealed that he and Njeeri were going through a divorce.

Many tributes have been penned about him, and Prof Amuka, his former student, had a deep message to share: “Rest in peace my mentor after a life of trying to shape the world with the might of the barrel of the pen.

You were too humane and kind to be a practicing politician in a world where the command of the gun rules.”

Also read the first article in this series --> Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Life and Times

And the second one in the series --> Exiled Ngugi: From Ngaahika Ndeenda troubles to an international career

You may also check out this one --> A bond forged in prison: Koigi’s tribute to Ngugi Wa Thiong’o

Also check this out --> 5 things you should know about Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o